Interior design isn’t just about making spaces look pretty. Usability and accessibility are key factors that are often overlooked in favour of aesthetically pleasing designs that aren’t quite so functional. Particularly for homeowners who have family members living with dementia or other health conditions, accessibility is a crucial consideration during a home renovation.

Noticing a serious lack of knowledge about dementia-friendly home design and inspired by their own experiences as carers, the team at Lekker Architects set out to collate affordable, achievable tips and ideas to design homes for people with dementia.

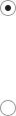

They joined forces with their friends from the industrial design studio Lanzavecchia + Wai and ultimately published Hack Care: Tips and Tricks for a Dementia-Friendly Home, an innovative and immensely helpful book formatted like the iconic IKEA catalogue. It even won Design of the Year at the President*s Design Award in 2023!

We caught up with the people behind Lekker Architects to find out more about Hack Care and how they are pushing for more accessible interior design that allows dementia patients to live with dignity while easing the work of carers and family members.

SquareRooms: Could you introduce yourselves? What kind of work do you do?

Lekker Architects: We are a multi-disciplinary design practice that combines insights from social science and design. We try to enable: to help people to live, play, learn and interact in new ways. We make buildings, books, services and experiences—and we conduct research in a think-tank called the Emotional Technologies Lab.

Can you tell us a little bit about Hack Care? What inspired this publication?

Hack Care was a collaboration with our friends, the industrial designers Lanzavecchia + Wai Studio. It is a book of ideas and resources to help carers for people with dementia.

It was inspired by our own experience caring for a family member—but also an awareness (shared by our collaborators at L + W and our clients at Lien Foundation) that few truly helpful books about everyday dementia care existed.

Why did you choose to design it like the classic IKEA catalogue?

There were a few reasons. The first was about positioning our book clearly, in a space that people wouldn’t find intimidating or specialized. We simply could not think of anything in the world of design more accessible or familiar than the IKEA catalogue.

At the time that the project began, most care manuals consisted of high-level principles that did not help with the endless daily challenges and stresses arising from progressive cognitive decline. We wanted a format that everyone could easily recognise and feel at home with.

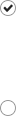

A second reason was more practical. When we started, care equipment—like specialised beds or chairs—was produced by medical tech companies, meaning that it was hard to acquire and punishingly expensive.

We needed to equip carers with useful objects that were cheap, easily available globally and covered all aspects of home life. We realised that adapting IKEA products was the perfect route to do this.

What are some of your favourite hacks for a dementia-friendly home that we can find in the book?

There aren’t really “top” hacks. Dementia is a remarkably idiosyncratic disease, meaning that some people manifest certain symptoms while others do not.

The book is designed to meet this problem, by dealing with daily life in a thematic way. We talk about eating, interaction and marking time, for example.

Many have told us that they found the Poang (reclining chair) hacks useful because most people with dementia spend much of the day seated.

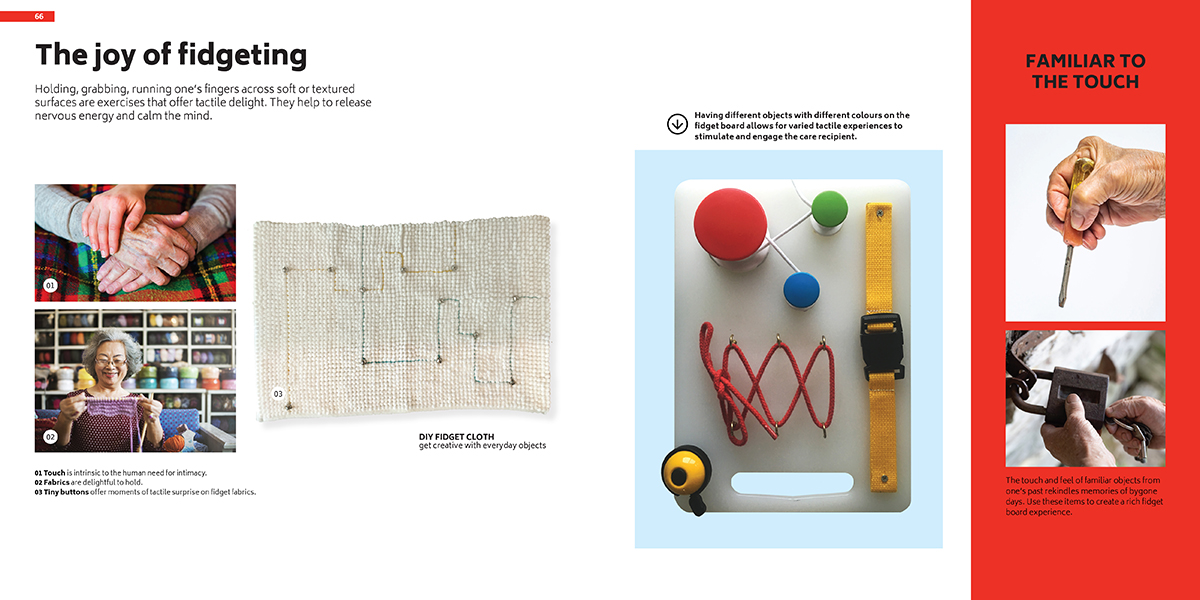

Others found the guide to “fidget boards”—surfaces with textures and objects to play with—helpful, as it can work to mitigate stress (another common issue).

Did you discover anything about living with dementia that surprised you while you were working on Hack Care?

There are many surprising aspects. Dementia really involves a total transformation in the way that people experience life. Part of the process involves what psychologists and artists call “defamiliarisation,” meaning that things we take for granted suddenly become new and strange.

We learned that many people with dementia have acute anxiety in the evening, for example, when the light changes. This is called the “dusk crisis” in dementia care. Similarly, areas of dark tone on a floor can be perceived as holes or gaps.

It is frightening, and fascinating, to imagine that we might begin to experience familiar experiences of time and space in such different and menacing ways. These are all topics that we discuss in Hack Care—in part because this is the kind of information we wished we’d had when we began our own care journey.

What are some things most homeowners and even designers don’t know about designing for people with dementia?

We feel that most designers, ourselves included, are only beginning to understand how to design for dementia. It’s not simply a matter of tricks or intel—that is, how to “solve” the problems that pop up. It’s more about making very difficult choices that affect the autonomy of a loved one.

How much do we limit their control of the environment? How do we balance more independence with the increased danger that comes with it?

These are not questions with singular answers, because they also depend a lot on the person and the family context. To make matters more complex, dementia is different for each person, and the effects and symptoms change continuously.

We don’t feel that this is a situation that can be “solved,” in design terms. And this is why Hack Care works as a demonstration of ingenious ideas—most of which came to us in watching other carers at work or speaking to them about their experiences.

We hope to draw attention to a creative method of solving problems as they arise, rather than offering a one-size-fits-all method or process that won’t work in many cases.

You emphasise living in dignity, even with dementia. What are some ways caregivers can make their dementia patients feel more dignified at home?

In the simplest sense, it is about preserving social relationships. Dignity—or love—are qualities manifested through relationships. These, in turn, happen through a myriad of tiny daily exchanges, or simply by being present in the same space.

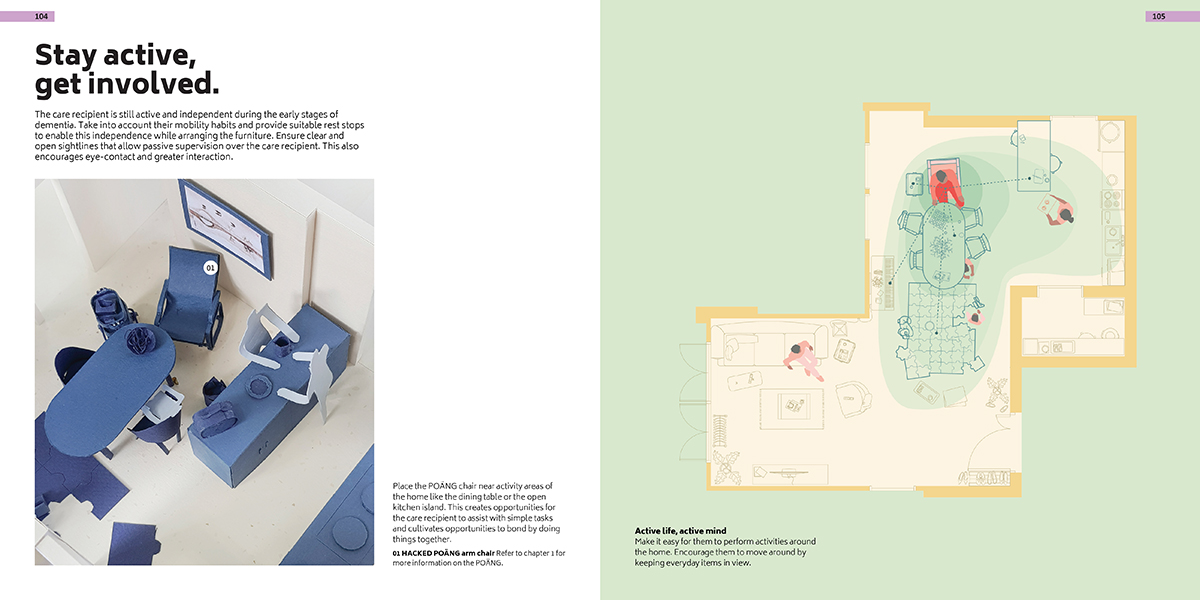

In Hack Care, we show approaches for re-arranging the home (modelled in this case on the HDB flat) so that the person with dementia remains central to the buzz of daily life.

There is an inevitable tendency to marginalise, which often grows simply from wanting to keep our loved ones safe or comfortable. “Care” often involves putting someone in a bubble, or making them dependent.

We have tried to show various ways that a person experiencing cognitive decline can remain spatially and socially engaged within the hubbub of the family.

What do you recommend for families with a really tight budget, who may not be able to afford accessible and dementia-friendly upgrades at home?

It’s very important to understand that dementia is an extremely expensive condition—and for many families, paying for it adds yet more stress into the mix.

The book is intended to address precisely this question; we show the cost of items used in the hacks so that carers and families can consider what scale of domestic tweaking is possible at any given time.

We think it’s essential that upgrades are “modular,” in the sense that they can be completed in phases. This is why we’ve shown how to assemble a series of wall-mounted objects for stability, for example (rather than spending thousands of dollars installing a continuous metal grab-rail).

Modularity is also a key quality because dementia is a progressive condition—meaning that the home will need to be continually “hacked” to keep our caring responsive.

Beyond dementia, what are some simple, low-cost accessible home design practices all homeowners should implement to make their homes welcoming and inclusive?

It really depends on who we’re welcoming. Being “inclusive” is a paradox, because different people, at various stages of life, have conflicting needs.

Our world is increasingly neuro-diverse—autism and ADHD are conditions on the increase—and many people experience hypersensitivity. Keeping a calm and minimal visual and acoustic environment is very important for their comfort.

On the other hand, many others are hypo-sensitive and find minimalist spaces enervating and oppressive. Sadly, there’s no design language that works best for all.

When we design spaces for diverse groups (with opposing needs) to share, we often try to make them as flexible as possible, with elements that can be re-arranged or removed.

We find, also, that having multiple ways to occupy the same room helps a lot—little nooks and niches at the edge of more open-planned areas will make many people feel cosy and secure.

Are there any current interior design trends and practices that you find very inaccessible? Do you have any alternatives you can suggest to homeowners and designers looking to follow those trends?

When it comes to domestic spaces, this isn’t so much of an issue. But there have been trends toward hyper-mediated retail spaces, where design guidelines encourage an explosion of materials, video walls and lighting.

These are designed to generate a sense of excitement, but it’s good to remember that this trend can be anxiety-inducing for many people. These spaces aren’t just bad for the non-neurotypical—they often induce fear or aversion in older adults too.

Are there any more tips you have for families with dementia patients that you didn’t include in Hack Care?

We’d always encourage family members to join WhatsApp chats with others in the same situation. That’s where the real knowledge is shared.

Can you recommend any resources for homeowners and designers who want to learn more about accessible home design and living with dementia?

We’d encourage them to check out FI&LD, an exhibition that we will be curating for Singapore Design Week, at LaSalle College of the Arts, from 21 October to 1 November.

There will be a wide range of amazing work by inclusive designers, hailing from different fields. There will also be live QR codes and resources available to explore more in the categories of Care, The Senses, Emotion, Social Life and Fun.

Find out more about Hack Care at hackcare.sg.