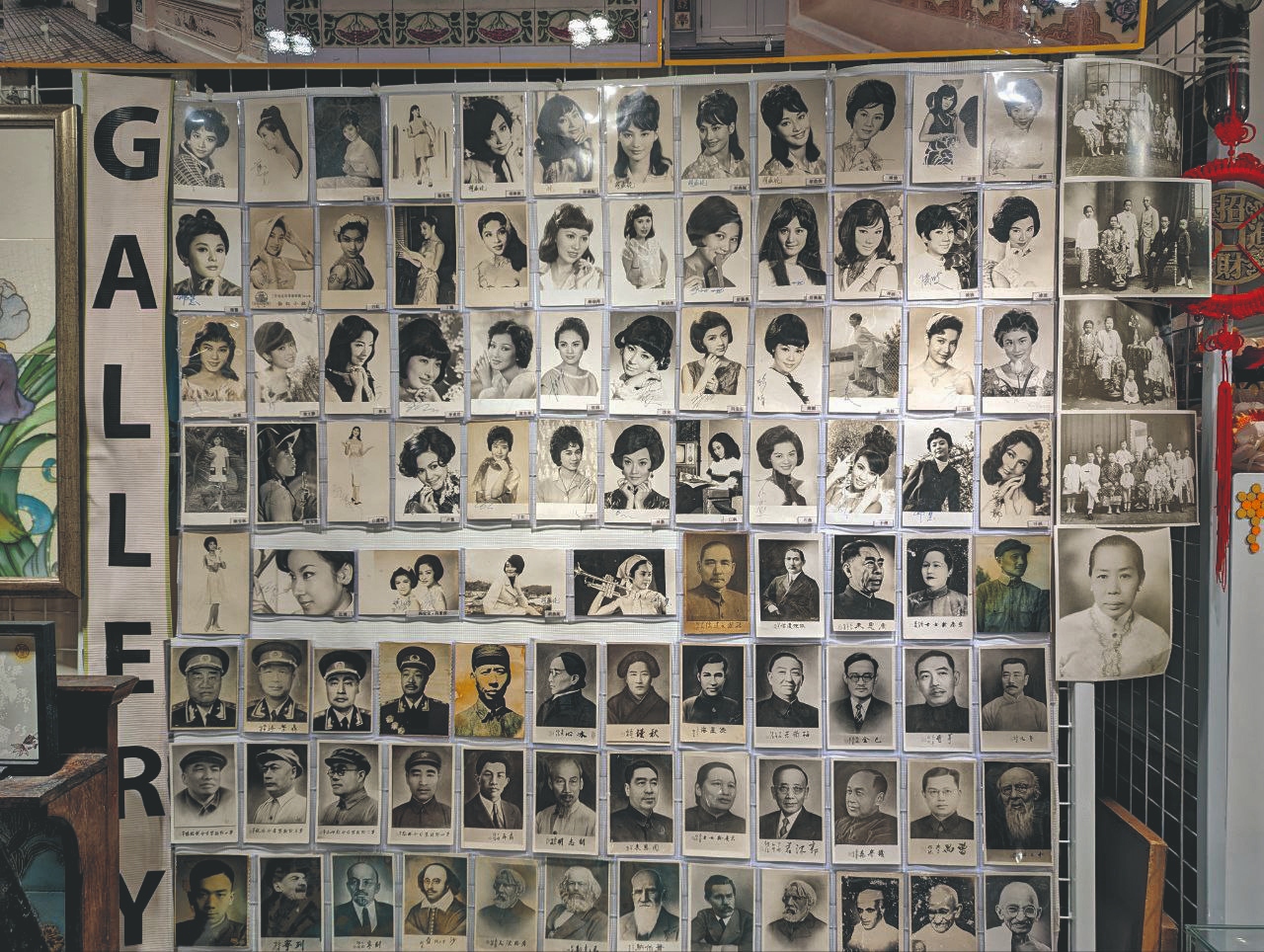

The Peranakan Tiles Gallery is more than just a tile shop—it’s also a museum, preserving heritage tiles in a city that likes to tear down, discard the old and build anew. The gallery’s irreverent custodian, Victor Lim, shares how he keeps a slice of Singapore’s history alive.

SquareRooms: The Peranakan Tiles Gallery is quite iconic. What’s the origin story?

Victor Lim: I have been collecting Peranakan tiles since I was young, starting in 1979 when they were demolishing the houses in Marine Parade.

I passed by the construction site and saw a lot of good items and thought it would be a waste to throw them away. So I picked up one or two pieces, which eventually became two to three hundred pieces.

When I visited Europe in 2008, I went to some antique shops to browse. I brought some of the tiles back home and then got the idea to sell the Peranakan tiles that I’ve collected over the years.

Tell us more about the history of Peranakan tiles.

Actually, we only call them Peranakan tiles in Singapore. We don’t call them that in Indonesia, Japan or England. This is a very technical issue and we could talk about it the whole day.

When our forefathers first saw these tiles on Nonya houses between the 1800s and 1930s, they didn’t know what to call them. They ended up calling them Nonya tiles, or “Nonya zhng” in Hokkien. Some people called them “Baba zhng” instead.

It was only through The Peranakan Association that the Nonya zhng finally became known as Peranakan tiles in the 60s.

Back in the day, what was the significance of the motifs on Peranakan tiles?

Take the fruit symbols, for example. Pomegranates and grapes symbolise fertility because of the seeds. Peaches symbolised longevity. Pineapples symbolise wealth. The banana is called “kim jio” in Hokkien, which sounds like an invitation to wealth. Apple is translated as “ping guo” in Mandarin, as in “ping an,” which means safety. There are also bats in the corners of some of the tiles.

Bats translate to “bian fu” in Mandarin, with “fu” representing fortune. As you can tell, the majority of the symbolism has to do with Chinese culture.

What’s the restoration process like?

First, we remove the tiles from the walls of the demolished buildings. How are you going to remove the cement? Nobody will do it because it’s so thick. You need to remove it perfectly, which is not easy. You need to have the passion and patience.

After you remove the tiles, you soak them in water for two to three weeks to soften the cement. In the past, I used a chisel to tease it out after. Now we have electric grinders. Once that’s done, you need to clean the surface, soak it in battery water and polish it. Keep on polishing.

Sometimes, when it’s too ugly, we need to refire it. The colour varies with temperature. When the temperature is too low, the colour doesn’t show up. To get the perfect piece, the temperature must be exact. About 970 degrees Celsius.

Each lot takes about 60 days to restore. And if it rains, we have to start over.

Who are your customers?

We get both Singaporean and foreign customers. Some fly in from Japan in the morning and fly back in the evening—it’s a day trip for them.

We’ve got contractors, designers, developers and architects behind projects including Changi Airport, Kampung Admiralty, Singapore Chinese Girls’ School and Catholic High School. My latest project is Mandarin Oriental Singapore. When it reopens in September, you can have a look at the swimming pool area. They’re all my tiles and very beautiful! Sometimes our customers send me pictures from New Zealand, Australia, America and England. I want the Peranakan culture to be known all over the world.

Why do you think young people have taken to Peranakan tiles?

It partly has to do with The Little Nonya. We saw a spike in business because of that show. Because it has been their number-one hit for so long, visitors from China have also been coming here for the last two to three weeks. It’s free marketing for us.

Are your children going to continue your legacy?

They’re not interested. If I let them take over, they will sell everything at a very cheap price. They have already informed me: “Now you sell them at $100, later I will sell them at $10.” But they deal with restoration in their own way, specialising in electronic guitars.

When do you plan to retire and what will happen to the shop?

Maybe in three to four years. I’ll see who wants to take over. There have been a lot of interested buyers, but they’re all quoting me numbers way below the market price. Many bad people out there!